ElectraTherm, Inc. appeared to be just one of many exhibitors at a big geothermal conference in Reno a few weeks ago, but founder and chief executive officer Richard Langson calls the event his company’s coming-out party.

Now the Carson City business is moving quickly to set up a distribution system and ramp up production.

The product sounds as irresistible as the legendary perpetual-motion machine: a unit that captures waste energy and converts it to electricity with zero emissions.

The technology, Langson says, can capture waste energy from a host of sources — hot water from geothermal wells, factory waste from smokestacks, flares burned off from oil wells, even facilities that step down the pressure of natural-gas lines — and convert it to electricity.

Two years ago, at the same geothermal conference in Reno, Langson found the missing link in his venture.

Professors at City University of London, a premier institution for pressure design, came to Reno looking for a business able to commercialize their academic research.

Langson, who’d spent 25 years experimenting with a technology that wasn’t as good as that of the British researchers, signed a 20-year licensing deal for the City University patent.

“What made this project take off is high oil prices,” Langson says. “When oil was cheap, you couldn’t sell this to anyone.”

Demand was fueled further by new state laws that require utilities to tap renewable energy sources. And a law recently passed in California qualifies waste heat as a renewable energy source — and subjects those who don’t reclaim it to criminal charges.

Initially, the federal administration was a huge obstacle, says Langson. “Until 10 months ago in the U.S., the president denied global warning was real. That’s why I went to Europe a lot because they’re so far ahead of us. They’re the leaders in green technology.”

He says as much as 50 percent of the energy used in the United States is wasted, and he says recovery of wasted heat could replace 92 coal-fired power plants.

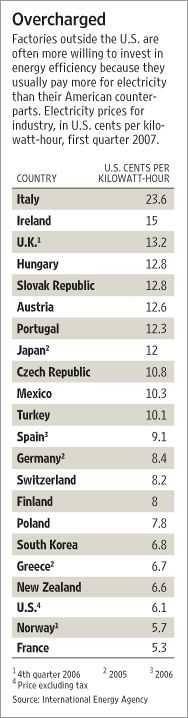

The company says an ElectraTherm modular power plant comes in with the lowest cost for alternative power generation: 3.5 cents per kilowatt hour. Compare that, Langson says, to solar at up to 45 cents, biomass at up to 12 cents, geothermal at up to 7 cents, and wind at 5 cents. The company’s systems start at about $50,000.

The company signed its first customer 10 months ago, a Texas oil well firm tangling with hot water in its wells. The ElectraTherm unit turns a nuisance — it’s costly to reinject the hot water to get rid of it — into a profit.

ElectraTherm maintains a 5,000-square-foot test facility in Carson City and operates a 10,000-square-foot manufacturing plant in Mound House. Langson is looking for an additional 25,000 square feet by year-end.

The company employs 45 — three full time engineers and 25 consultant engineers, plus 20 workers at the fabrication shop in Mound House. A current task is setting up sales-and-installation distributors. Although the units are modular and ready to go, it takes a service truck plus basic plumbing and electrical know-how.

Another goal: bringing on a chief executive officer to run the business and oversee a three-year expansion plan. “We just started building production units,” Langson says. The goal is to sell 34 units next year, priced from $50,000 to $1 million each, depending on capacity. The second year goal is 347 units. And in year three, 600 units, then 1,200, continuing to double production each year.

Employment is expected keep pace, growing to 125 people in 18 months, and up to 250 by year three. Langson also expects positive cash flow within 18 months.

Rapid growth takes cash, and investors in the privately held company will fund it.

Eventually, Langson says he’ll build a larger production facility on property he already owns near the Carson City airport.

“I’m working with the mayor and governor to keep the manufacturing in Nevada,” he says. “I want to stay here; I don’t want to be on the airplane all the time.”

Although not a trained engineer, Langson spent 30 years in the construction industry erecting buildings, bridges and dams. While engaged in a drag racing hobby, he built his own dragster.

“After 45 years of doing that, I became a mechanical person. I’m not an engineer. I’m a tinkerer. I can make it work,” he says. “I’m a businessman. I’m doing this to make money. But if I can save the world, too…”

Friday April 29, 2005 Houston hosted an event unlike any other the city has seen. The event was a one day symposium held at the George R. Brown Convention Center to take a close look at green building on the Texas Gulf Coast. Gulf Coast Green, organized by the American Institute if Architects Houston Chapter Committee, the U.S. Green Building Council and others, brought in an incredible line-up of local and national speakers that included engineers, contractors, and commercial and residential architects. The event also featured a Construction Technology Expo showcasing the latest green building products, services and technologies from vendors.

Friday April 29, 2005 Houston hosted an event unlike any other the city has seen. The event was a one day symposium held at the George R. Brown Convention Center to take a close look at green building on the Texas Gulf Coast. Gulf Coast Green, organized by the American Institute if Architects Houston Chapter Committee, the U.S. Green Building Council and others, brought in an incredible line-up of local and national speakers that included engineers, contractors, and commercial and residential architects. The event also featured a Construction Technology Expo showcasing the latest green building products, services and technologies from vendors.